Afterlife fantasies—from Dante’s Divine Comedy to Pixar’s Soul—have always been a unique way to look at society. In this short series, I’ll be looking at the film tradition of afterlife fantasies, and discussing the recurring themes and imagery across a century of cinema.

In the final post in the miniseries, I’ll look at the way two very different films are taking afterlife imagery into the future. One is the movie that inspired this whole thing, Pixar’s Soul, and the other is Lil Nas X’s “Montero”. Am I stretching the definition of movie a little? YES. But first, I think it’s an important work, and second, I think it’s fascinating that two recent explorations of afterlife imagery go in radically different directions to come to the same point. I was about halfway through my research when “Montero” hit, and was a fun bit of pop cultural convergence that I couldn’t pass up.

Join me on a journey through The Great Before, The Great Beyond, Heaven, Hell… and Montero.

You’ve Got Soul…But What Does that Mean, Exactly? Pixar’s Soul

Now before I get into Soul I want to acknowledge that there are certain elements of it that I can’t speak to. Some of those have been discussed by my colleague Andrew Tejada here. What I can talk about is how this movie takes imagery from past afterlife fantasies and updates them.

Much like the central characters in Here Comes Mr. Jordan and its remakes, Joe dies on the same day he finally gets his Big Break. But here the Big Break feels even more vital, because Joe sees his current life—teaching music, spending time with his mom, dating a bit—as a prelude (or even Great Before) to the jazz career that will be his REAL life, when he can play for paying audiences who will recognize his passion for music, and agree with his that jazz has been his life’s purpose all along. As in most of the movies before it, death itself is softened—we see Joe fall into the manhole, but then it cuts to his blue blob soul floating in darkness.

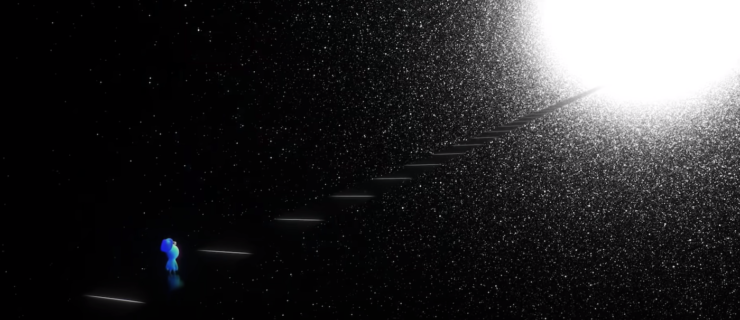

Suddenly he’s on a staircase, which is very reminiscent of A Matter of Life and Death’s. When he meets three fellow deceased people, one of them even speaks French, saying “This beats my dream about the walrus” and everyone clearly understands her, just as the British and French airmen understand each other in the reception area of Matter’s Other World. (Also, can we hear more about that walrus dream?)

As in Here Comes Mr Jordan, the other dead are clearly ready to go. One woman is even looking forward to it after living for 106 years.

We never glimpse the Great Beyond, just a mass of light at the top of the stairs, and as the other blue souls get close to it they become opalescent, their faces fade out, and they zap into the light. They look pretty happy about this, but Joe shrieks and runs back into a mass of dead souls. Joe is the only one we see fighting it, pelting down the staircase a la Peter Carter in Matter, yelling “I’m not supposed to be here!” and “I’m not dying the very day I got my shot! I’m due! Heck, I’m overdue!” and “I’m not dying today—not when my life just started!” as the stairs inexorably carry him forward.

This all happens before the credits. They’ve packed Joe’s entire life and motivation, his death, a bit of cosmology, and detailed riffs on two other afterlife fantasies into the opening minutes of the movie.

But then Joe does something that none of the other afterlife protagonists have ever done: he breaks out of the afterlife. In Defending Your Life, Daniel Miller runs to Julia’s tramcar, and is allowed entry into the next world because he’d finally overcome his fear and grown as a person. He finally did what the afterlife bureaucracy wanted him to to do all along—just a little later than they were hoping. In What Dreams May Come, Chris hires Tracker to guide him to Hell, but there were no rules against that, because there don’t seem to be any rules in that particular afterlife. And in Wristcutters, Zia is freed by a Person In Charge as an act of mercy. In Soul, though, Joe doesn’t attempt to go into The Great Beyond and then make his case. He doesn’t have a loophole like Peter Carter, or Joe Pendleton, or Lance Barton. He just flat out refuses to go, and dives off the side of the staircase into the void.

It’s fucking great.

And unlike the other afterlife fantasies I’ve covered, this one actually takes an extra step to show us more of the universe. As Joe falls, he’s sometimes in a void, sometimes in line drawings, and sometimes in scenes that riff on the ending of 2001: A Space Odyssey. He passes through all of this before portal opens and drops him into The Great Before. We don’t see anyone open the portal—was it simply tripped as he approached it, like an automatic door? Was the universe itself aware that there was a soul gumming up its works?

While the movie balked at revealing what lies beyond death, it’s only too happy to show us The Great Before. We meet Jerry (“the coming together of all quantized fields of the universe, appearing in a form your feeble human brain can comprehend”) and then realize that there are a lot of Jerrys, presumably one consciousness expressing itself in different forms and voices—including, in a moment of genius on the part of the Universe and/or the PIXAR casting people, that of Richard Ayoade.

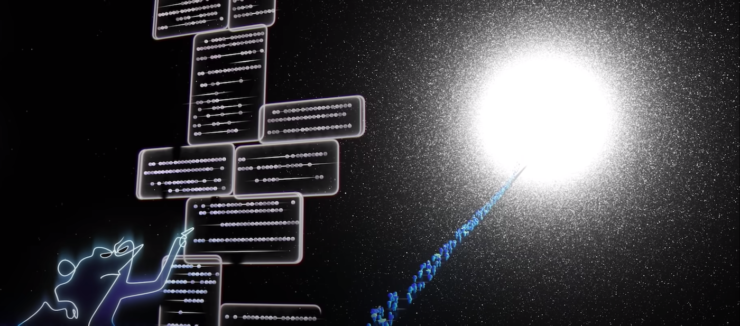

The Great Before turns out to be reminiscent of Defending Your Life—sort of a No-Judgment City—complete with enormous halls and theaters for Mentors to review moments from their lives and new souls to learn about life on Earth. Rather than a Past Lives Pavilion, the baby souls are ushered through different Personality Pavilions to pick up traits like aloofness and megalomania. When Joe is mistaken for a Mentor, he has to sit through a terrible orientation video that explains the Hall of Everything and Hall of You. If reincarnation exists in this universe, it’s not discussed here, because the souls in the Great Before are all “new”, and the Hall of You only shows moments from Dr. Bjornsson’s life, and then from Joe’s.

The movie’s throughline is a battle between individuality and bureaucracy, which gradually turns into an interrogation of what “individuality” means. Joe is determined to get his shot as a jazz musician because music is his “spark”—the reason he’s on Earth at all. His need to express that is in direct opposition to Terry, the Accountant who, like the unseen Registrar in Here Comes Mister Jordan, or the Chief Recorder in A Matter of Life and Death, has to make sure all souls are processed as people die. Terry’s sole motivation is in keeping the count, and making sure the numbers match up. When they don’t, Terry takes that personally, and visits a hall of records that includes, seemingly, every soul on Earth. This hall, like the books lining the shelves in Heaven Can Wait or the files in Wristcutters, implies a certain kind of order. There is a comfort to be found in the idea that every single human who’s ever lived has a file somewhere.

And for all that the movie kind of presents Terry as a villain, when they actually catch Joe and 22, Terry explicitly tells Joe “You cheated.” Which is true. Joe’s had a life. It isn’t anyone else’s fault that he lost sight of joy and meaning as he pursued his music career. He wasn’t accidentally taken too early, or lost long enough to fall in love, or hit by a car while administering CPR. He, like Daniel, died fair and square.

The Jerrys, ever kinder than Terry, give Joe a moment to say goodbye to 22, which gives her the chance to chuck her card at him and storm off, and one of the Jerrys a chance to chuck some wisdom at him: “We don’t assign purposes—where did you get that idea? A spark isn’t a soul’s purpose! You mentors and your passions! Your purposes. Your meanings of life! So basic…”

And then the movie, unlike all the movies before it, breaks its own rules to give us a satisfying ending. I mean, I assumed going in that Joe wasn’t going to stay dead at the end the film, but I was pleased with the way the writers tied up the loose ends. Joe does the selfish thing. He cheats his way back to life. But there’s no immediate punishment for cheating—he plays an excellent set, his mom cheers him on, he ends the night with his dream job. But then he suffers the thing most artists suffer when they finally Do The Thing—whatever The Thing is—and realize that life rolls on around you and it doesn’t feel as momentous as you thought it would. This is summed up in Dorothea telling Joe a slightly edited version of the parable of The Little Fish:

“I heard this story about a fish. He swims up to an older fish and says: “I’m trying to find this thing they call the ocean.” “The ocean?” the older fish says, “that’s what you’re in right now.” “This”, says the young fish, “this is water. What I want is the ocean!”

This is a story that was told by Jesuit Anthony de Mello in his book The Song of the Bird, and later quoted in The Jesuit Guide to (Almost) Everything by priest/Chaplain to the Colbert Nation James Martin, which is where Pete Docter found it. (An adaptation of this story also forms the core of “This is Water”, the David Foster Wallace commencement speech that your aunt probably forwarded to you a few years ago.) In a film that resolutely shies away from a particular theology, it’s interesting to note that they went with Eastern-tinged Ignatian spirituality for the big fulcrum moment—and it’s this story that pushes the movie into a truly unique moment. Joe, still reeling from existential panic, finds 22’s mementos of her day on Earth. He puts his own worries aside and begins playing a song for her, hoping that he can reach the Zone and find her.

A lot of people talked about crying during Soul. I didn’t, because, as I think I’ve mentioned a few times, I am by nature a sarcastic bag of meat; my heart is dead, and my tear ducts are, basically, carved from stone.

However.

When Joe communes with 22’s memories, he remembers the important moments from his own life. In a correction to his time in the Hall of You, he remembers how life felt to him in those moments, without the weight of his plans and aspirations. He essentially becomes his home, his mom’s shop, the Half Note. Then he becomes New York, the U.S., the world, and, finally, the galaxy.

I’ve been stuck inside for a year, like a lot of people. I’ve been lucky enough to be stuck inside for a year. My city has teemed outside my window, and I have done my best to help keep it safe by not experiencing it. And in the interest of brutal honesty I have to admit that when the “camera” zoomed out to show all of Manhattan, and zoomed up the Chrysler Building and panned over Central Park with all the light of the City around it, I may have made a sound suspiciously like “mmmph.” I may have had to blink a couple times.

But the scene is more than just a patented Pixar tear duct-poke. The scene starts with 22’s fallen seed pod and only gradually works up and out into the stars. It’s a perfect way to express the interconnectedness of life, to show Joe’s connection to 22, and to tie ineffable stuff like the Zone and the Great Beyond and the Great Before into physical, observable life. It’s also a gorgeous reversal of A Matter of Life and Death, with its perfect opening line: “This… is the UNIVERSE. Big, isn’t it?”

Which makes it all the more fun that this is where the movie decides to go the route of Matter and Defending Your Life before it, and allow our protagonist to defy the universe and get away with it. The movie doesn’t explain how Joe has 22’s memories—I take this as a gentle nod to Here Comes Mr Jordan and its remakes, where all the protagonists end up “becoming” the people they replace in the end—but 22’s memories, the experience of a new soul on Earth, are what knock Dorothea’s words into place. The idea of the “spark” being untied to purpose, the idea that we’re all swimming in the ocean, isn’t just a platitude characters trade back and forth and think about—Joe has to experience it to understand. And having had that experience he immediately turns it into music, because his art has to be the vehicle to fix his mistake.

And having apologized to 22, sent her on to Earth, and returned to the Stairway, the Jerrys decide to be nice and give Joe another shot at his old life. In true Mr Jordan Universe style, 22 will forget about Joe, and all of her adventures and thousands of years in The Great Before. But Joe, as far as we can tell, is sent back to life with at least some knowledge of everything he’s just gone through. All of the work he did on himself over the last few days is part of his growth, the healthier relationship with his mom, the way he stood up for himself (if a bit rudely) to Dorothea, and the way he absorbed her advice after the gig. It’s all evident in his face when he steps out of his door in Queens—having battled death, and won, he’s a new person.

Montero

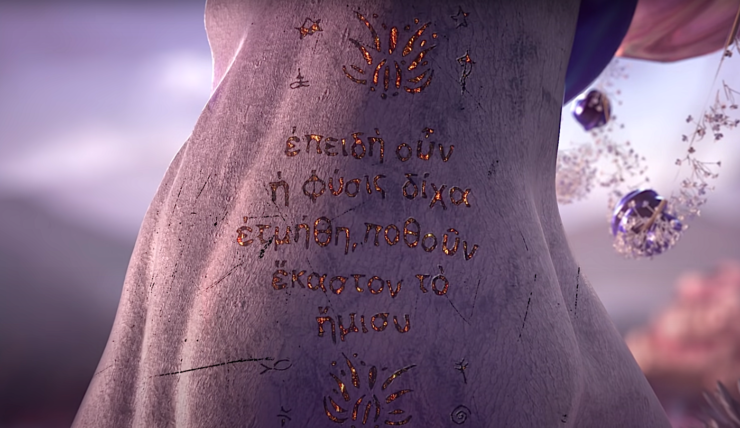

Lil Nas X shows how the imagery of afterlife can be used to comment on current society and human individuality. In “Montero (Call Me By Your Name)” his lyrics combine a couple of common queer experiences: the thing where you’re in love with someone who only reciprocates in private, and the thing where you’re attracted to people who are who you want to be. But in a gorgeous act of juxtaposition, the video speaks to a very different queer experience: being told to be ashamed of yourself, and being told you’re going to Hell for who you love. Lil Nas X takes the imagery of the Garden of Eden, Heaven, and Hell, and uses them to tell a narrative of self-acceptance. The Tree of Knowledge has a line from Plato’s symposium carved into it, like lovestruck kids might carve a heart and initials:

Which, as far as my research has told me, is the bit from Plato that goes: “So in the beginning when they were cut in two, they yearned for each other’s half”—in other words, the inspiration for Hedwig and the Angry Inch’s “Origin of Love.”

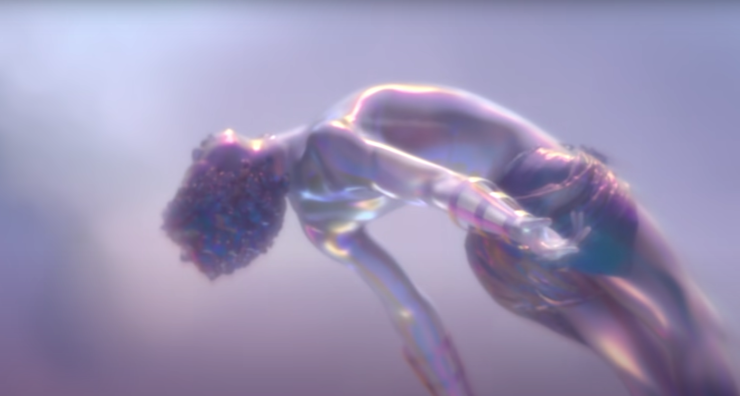

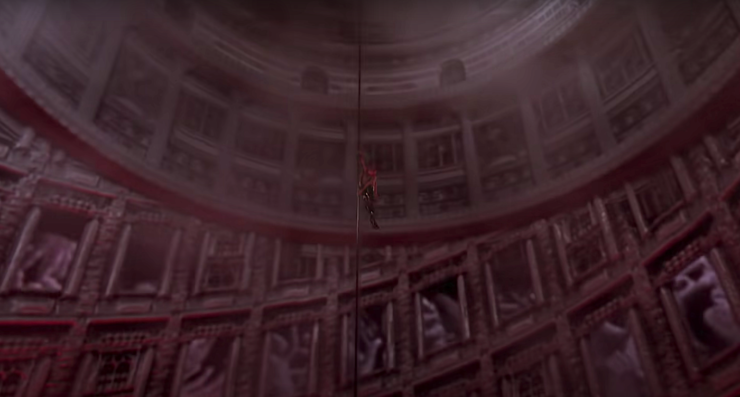

Which is a great start for a video. Then the snake is reimagined as a purely sexual seducer, a positive character in the sort of Gnostic/William Blake kind of way that he opens Lil Nas’ eyes to a new kind of life. He’s condemned in a Hunger Games coliseum, where he’s the only pink-haired person among a sea of blue, and, having been stoned to death—presumably for his queerness, his refusal to conform, or both—rises to Heaven. As in Soul, the character’s body becomes luminous and opalescent as it gets closer to The Great Beyond:

But here’s where the true innovation comes: Lil Nas doesn’t enter Heaven, and it doesn’t look like anyone’s rejecting him—he chooses to leave. And rather than using the traditional staircase of A Matter of Life and Death, the elevator of Heaven Can Wait (1943) and Angel on my Shoulder, or even the vague tunnel of What Dreams May Come and Heaven Can Wait (1978), Lil Nas steps into the future and opts for a stripper pole.

The pole becomes an axis mundi, symbolically linking Heaven, Earth, and Hell and creating a similar metaphor to that of Yggdrasil in Norse lore, the Tree of Life/Knowledge of Good and Evil, or even the Christian crucifix. He slides down to confront a fairly passive Satan who functions more as symbol of internalized homophobia (his throne sits atop more Greek text: “They condemn what they do not understand”) than a person who would punish sin. Having lapdanced the Devil into submission, Lil Nas snaps The Fallen One’s neck and takes his crown, becoming ruler of Hell. A perfect reply to all the people who told him he was going to Hell for being gay.

This is a bold step in the tradition of the afterlife fantasy. Each of these stories is, at heart, the same: “regular old death/afterlife is fine for the suckers, but I’m different”. But “Montero” is the first one since A Matter of Life and Death that shows the protagonist rejecting the promise of Heaven—and Lil Nas isn’t rejecting it for love like Peter Carter did. He’s also not simply balking at Death in general because of unfinished business like Joe Gardner, the Joes Pendleton, or Lance Barton—he’s rejecting it to reclaim his own self-worth and identity.

***

When I first thought of doing this series, I was focused on the idea of looking at trends in the subgenre – was there an uptick in afterlife fantasies right after wars or other global tragedies? How did the imagery of the afterlife change? Each narrative finds a way to grapple with death via characters who somehow outwit it, or at least retain some level of control over it. At the same time, each story uses its afterlife to poke at soft spots in culture. And what surprised me was just how much the movies seem to follow a template, and also how many of them seem to be untouched by their era. Obviously, Between Two Worlds and A Matter of Life and Death are both very much World War II-era movies, but What Dreams May Come and 1943’s Heaven Can Wait could come out tomorrow and be just as relevant, and Here Comes Mr. Jordan has been rebooted over three generations while keeping its core storyline intact.

What I’ve come away with is that even in the midst of dealing with cosmic bureaucracies and wacky body-swapping shenanigans, each of the films stakes its meaning on the importance of human individuality, and the idea of trying to express a sense of a human worth beyond corporality. Peter Carter, Henry van Cleve, Joe Pendleton, Annie Collins-Nielsen, Zia, Mikal, even Eddie Kagle—all of them are worthy of second chances. What I’m really excited by is seeing how Soul and “Montero” took that aspect and ran with it. Soul #22 gets as many chances as they need to finally come to Earth, and Joe Gardner is allowed to return to life just to live it, not necessarily to become a jazz great. The protagonist of “Montero” travels through realm after realm, learning to have pride in himself for who he is. When faced with all the clockwork of the universe, all of them plant their feet and refuse to be cogs.

What I’m hoping for going forward is that more fantasies mine this material, and follow the lead of What Dreams May Come and Soul to create ever-more-unique visions of before worlds, after worlds, in-between worlds—as long as we all have to cope with death, we might as well do something cool with it.

Any day that Leah Schnelbach manages to write about Richard Ayoade and Lil Nas X is a very good day. Come dance with them on the demonic pole that is Twitter!